Buddhist Economics All People Matter

Buddhist Economics: is giving people a chance to use and develop their skills; enabling them to overcome their self-centeredness, joining with others in a common task; creating the goods and services needed for a fair existence—a simple way to say it is a compassionate approach to business.

Buddhist Economics: is giving people a chance to use and develop their skills; enabling them to overcome their self-centeredness, joining with others in a common task; creating the goods and services needed for a fair existence—a simple way to say it is a compassionate approach to business.

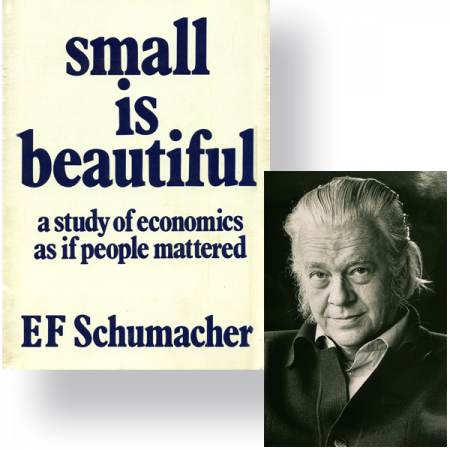

EF Schumacher was probably the first person to use the term, ‘Buddhist Economics’—in his book, Small is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered [1], published in 1973. I was fortunate enough to meet him briefly when he was chief economist at the British National Coal Board (NCB), which was set up in 1946 with sole responsibility for managing the British coal industry. The NCB was privatized as British Coal in 1986 and was dissolved in 1994. The industry employed over 1 million in 1920. According to IBIS World, today it employs 155 people.

Since then it has always seemed to me an irony that EF Schumacher should have worked in the nationalized fossil fuel industry, given his analysis and dismissal of the idea that ‘big is better’, as implied classical economics and the measurement of GNP.

Without having to read the whole book, you can read Schumacher’s essay on Buddhist economics on the Schumacher Center for a New Economics.

Is Buddhist Economics an Enlightened Approach to the Dismal Science?

In her book, Buddhist Economics: An Enlightened Approach to the Dismal Science [2], Clair Brown builds on Schumacher’s understanding of the term while focusing on what she sees as values, sustainability and equity. Her book emphasizes interdependence, shared prosperity and happiness. She describes the pursuit of happiness as, “creating meaningful lives for everyone within a healthy ecosystem.”

When I started work in the business world about 60 years ago, my employer aimed at competitive advantage. Competitive advantage was the cry of business aimed at people buying more and more stuff. I bought into the idea and never, I am ashamed to say, gave it a thought, let alone making any connection between the aim and my own happiness. Happiness was then measured even less than it is today. Even though we are ruled by Gross National Product, at least some people have begun to question its relevance to their lives.

Clair Brown points out that, “Buddhism does not prohibit being wealthy in the material sense, as long as we do not become attached to material possessions or monetary wealth of any kind, and we share our riches with others.” The wealthiest 1% of Americans controlled about $41.52 trillion in the first quarter, according to Federal Reserve data released in June 2022. Yet the bottom 50% of Americans only controlled about $2.62 trillion collectively, which is roughly 16 times less than those in the top 1%. The top 0.1% of Americans had an average wealth of around $43 million in 2020. This is an ugly consequence of an economy where the rules set by government do not favor the majority. Companies who practice Buddhist economics, even without knowing so, are rewriting the rules of business.

Is Consumption Beautiful?

If such a manifest inequality is ugly, I wonder what beauty would look like economically and in business? And so, I loop back to Fritz Schumacher and Small is Beautiful. In the book he says, “…the ideal from the point of view of the employer is to have output without employees, and the ideal from the point of view of the employee is to have income without employment.” United States Private Consumption accounted for 68.2 % of its Nominal GDP in March 2022, so it must be that we accept that consumption is good. Really? What about truth, goodness and beauty?

As Clair Brown says, “Enjoying life isn’t about how you spend your money; it’s about how you spend your time.” She would have us focus on wellbeing, rather than income. The truth is that traditional business does not focus on wellbeing, but on profit. When I had a business, I saw profit as a measurement of ourselves, not as an end in itself, but outside pressure was never to operate that way: the strength of the balance sheet mattered to the bank; the ‘bottom line’ mattered to the market.

A friend of mine, Dr Malte Krohn describes entrepreneurial mindfulness as the art of “being while striving”, believing that entrepreneurs have both great power and responsibility—doing well by doing good. I build on his insight and consider it as being, striving and thriving.

People and Profits

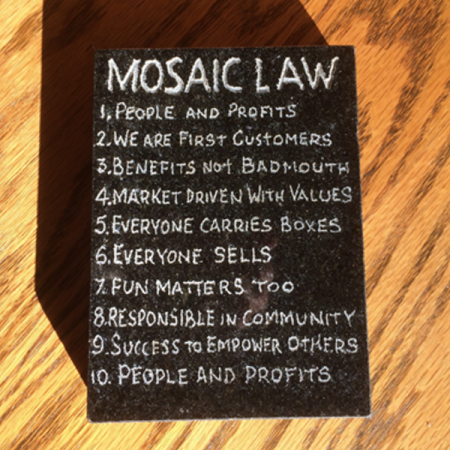

Though the business we founded in the 1970s did not survive long after our (the founders’) sale eleven years later, the values we espoused, lived on among the people who had been in it. The company name was Mosaic and we hacked out our modus operandi in the form of ‘Mosaic Law’.

Though the business we founded in the 1970s did not survive long after our (the founders’) sale eleven years later, the values we espoused, lived on among the people who had been in it. The company name was Mosaic and we hacked out our modus operandi in the form of ‘Mosaic Law’.

The first ‘law’ was “People and Profits” and the tenth was “People and Profits”, too. When we carved our ‘tablet of stone’, back in the 1970s, many business people thought us bizarre.

What is also true, is that we struggled to maintain those ‘laws’, just as I do now to maintain my personal values of a meaningful life. I have learned through years of meditation practice that we probably will never reach enlightenment and achieve the end of suffering, but the journey still counts.

My experience and observation tells me that all businesses are a journey rather than a destination, indeed a journey of discovery, provided that the leaders are awake and cherish progress. You’ll head a lot about ‘standard operating procedures’ as your venture progresses. They are important to ensure the repetitive and routine tasks are executed well, but do not let the idea permeate your thinking about the development of the business.Alex Edmans, a London Business School professor’s book Grow the Pie: How Great Companies Deliver Both Purpose and Profit is a book for every intending entrepreneur who looks for a way to both make the world a better place and make a profit; and to help build an economy for the people and the planet.

Buddhist Economics Involves Struggles

New ventures go through struggles and I observe that more and more startups are concerned with and dedicated to ‘how they spend their time.’ They are manifesting a way of Buddhist economics without even knowing that is what their efforts might be called. Buddhism and Buddhist economics acknowledge that life is a struggle—and so is entrepreneurship.

Struggles are good and striving is even better. I don’t know of any startups without struggles. The great thing about them though is that they are wonderful learning opportunities.

Service

Today’s entrepreneurs are still creators in the middle of their struggle. Most of them set out to change the world while they sell a better mousetrap, and know that the process of being in business is as important as the product they offer. We used to talk about entrepreneurs and social entrepreneurs as being different in kind, but the reality is that the majority of venture creators are different to those of the past and nowadays most new ventures are also social enterprises, or, you might say, applying Buddhist economics to their own venture.

Clair Brown puts it well, saying, “… you need courage. Courage to change, courage to protect the environment, courage to promote justice, and courage to live with joy.” If that’s not beauty in business, I don’t know what is. The Buddha’s Eightfold Path is one of the core teachings of Buddhism. I believe that is if you simply read them and reflect, you’ll see how wonderfully they apply to entrepreneurship and how they will lead your venture to thrive.

Here they are:

1. Right Understanding: seeing reality unfiltered—as it actually exists

2. Right Thought: the purifying wisdom and intention of harmlessness

3. Right Speech: saying the truth, practicing non-harm in your speech patterns

4. Right Action: non-harmful action—applies to self and others

5. Right Livelihood: commitment to a non-harming life

6. Right Effort: seeking the mindful discipline to improve oneself constantly over time

7. Right Mindfulness: awareness of reality and freedom from temptations, cravings, & distractions

8. Right Concentration: proper concentration and meditation.

[1] Harper Perennial; Reprint edition, 2010

[2] Bloomsbury Press; 2017